Photos by Lisa Saleme

Lee Jamison has lived in Huntsville for almost four decades, producing more than 2,000 works of art in that time. His work can be seen at many locations around Huntsville, as well as in Austin, Brenham, Houston, and other Texas cities. Although typically described as a regionalist, Jamison’s work combines philosophy, religion, and history; is occasionally abstract; and always offers intriguing depth and breadth.

Lee Jamison has lived in Huntsville for almost four decades, producing more than 2,000 works of art in that time. His work can be seen at many locations around Huntsville, as well as in Austin, Brenham, Houston, and other Texas cities. Although typically described as a regionalist, Jamison’s work combines philosophy, religion, and history; is occasionally abstract; and always offers intriguing depth and breadth.

When I was a small child, my mom gave me a copy of The Little Engine That Could, which has wonderful illustrations. And I loved it. I remember being two or three years-old and spilling orange juice on the book, and I was distraught. I loved that book and its illustrations. I think it was an important part of what made an artist out of me. It’s the power of putting an image on a sheet of paper or canvas, the capacity to communicate something important. Ever since then, I’ve reached for ways to tell a story through composition, color, and contrast—that is, through art.

How did you move from being a young child fascinated by art to becoming a working artist?

How did you move from being a young child fascinated by art to becoming a working artist?By the 5th grade, when I was living in Shreveport, Louisiana, I had become fully aware that I could tell stories with pictures. I particularly liked airplanes, and I would concentrate on how to make the sky and the ground look special. I remember my English teacher allowed me to do a book report with pictures. Many years later, I did a show in Shreveport, and that English teacher brought in my pictures from 5th grade that she had kept over the years. I was blown away that she kept those.

I first went to Lon Morris, and I graduated with a degree in art at Centenary College in Shreveport.

At first, I thought I would be a Methodist preacher, and that’s why having the opportunity to do the murals at the First United Methodist Church is so special to me. But that vocation was not to be; I realized my personality did not fit being a pastor. So I thought, “Well, I’ll be an artist.” You get to live hand-to-mouth, do all these self-sacrificial things, and family-sacrificial things. Who wouldn’t want that? No, but seriously, every day I have the chance to do what I love.

At first, I thought I would be a Methodist preacher, and that’s why having the opportunity to do the murals at the First United Methodist Church is so special to me. But that vocation was not to be; I realized my personality did not fit being a pastor. So I thought, “Well, I’ll be an artist.” You get to live hand-to-mouth, do all these self-sacrificial things, and family-sacrificial things. Who wouldn’t want that? No, but seriously, every day I have the chance to do what I love.

There are several things going on here. Sometimes pieces take several weeks, so you are talking real labor going into these.

Also, there’s the lifetime of experience that goes into the skill that allows an artist to create art. Many paintings lie fallow, remaining unsold and not producing income. But it comes down to how much you love what you do, and how much you are willing to sacrifice. And some pieces are more lucrative than others. A large mural can finance an artist for half a year if you don’t have lavish habits…

…and in Houston. I enjoy doing murals for museums, because it gives me an opportunity to study things deeply that I haven’t had a chance to learn about previously.

I’m a nerdy academic artist in that I like to explain things visually, things that many people would think of as esoteric. In Waco, for example, I did the murals of the Mammoths, and learning about those creatures and their world was fascinating. Similarly, when I did murals in Bastrop, I took time to learn local history before beginning the mural.

I went through the history of Bastrop with Ken Kesselus, now the city’s mayor, and included about 111 historical aspects in the mural, all told with images.

Yes, the Driskill was serendipitous. Someone had seen one of my murals at Scott Johnson Elementary here at Huntsville, and they thought I would be a good person for the mural at the Driskill. The hotel was doing a renovation project in 1996-1997, so I was able to do extensive work on the ballroom there. It was one of the best paying projects I ever did, and it was a great experience, except for the time away from my family.

That was special. At the time, my children were going to Scott Johnson, and I would occasionally go in to do art demonstrations. But it’s tough to truly convey art to young children, especially when you have limited time. I thought it would be good to do a larger project so students could see the process unfold and make a connection to it. I proposed this idea to Barbara Skeeters, who was principal at the time, and she loved it. Scott Johnson had recently passed away, but my children had attended his 100th birthday party the year before at the school. In fact, I had a photograph of my son handing Mr. Johnson the book of pictures the school kids had put together in his honor.  I was able to incorporate that moment into the mural, but the scope was much larger, being a visual history of African-American education in Walker County and, in fact, east Texas. It was a great educational project and an opportunity for young people to see how an artist approaches and executes his work.

I was able to incorporate that moment into the mural, but the scope was much larger, being a visual history of African-American education in Walker County and, in fact, east Texas. It was a great educational project and an opportunity for young people to see how an artist approaches and executes his work.

Yes, we wanted to do something both light-hearted and east Texas-y. We took the home’s dining room—which is usually a plain, white, boxy room—and gave it the visual form of a gazebo. I love it when children come through that home, and I can show them the vines hanging on the gazebo, the bird nests, wasp nests, and the slithery and crawly things. I used native species when deciding what to include.

Not all of your art is local-oriented. Your murals at the First United Methodist Church, for example, depict the creation of the world.

Not all of your art is local-oriented. Your murals at the First United Methodist Church, for example, depict the creation of the world.Yes, and it’s more abstract. Genesis isn’t really a story you can tell literally through photo-realistic pictures.  It’s much deeper than its surface appearance. It’s reframing the entire narrative of creation around a single Creator who is purposefully devising a Universe for His own creative purposes. How do you show in some literal fashion the breath of God blowing across chaos and creating order? You don’t, so I approached it more abstractly, while still managing, I hope, to capture an image of chaos, the breath of God, the coming of light, and a separation of the light and darkness.

It’s much deeper than its surface appearance. It’s reframing the entire narrative of creation around a single Creator who is purposefully devising a Universe for His own creative purposes. How do you show in some literal fashion the breath of God blowing across chaos and creating order? You don’t, so I approached it more abstractly, while still managing, I hope, to capture an image of chaos, the breath of God, the coming of light, and a separation of the light and darkness.  It’s a narrative told through abstract images emphasizing a monotheistic God.

It’s a narrative told through abstract images emphasizing a monotheistic God.

Art is a window on how we see things, and not just with our eyes. It’s how we frame an image of the universe in which we live. If I’m looking at something as an uninformed viewer, I’m seeing it for acquisition and avoidance. Generally, we look for things either because we want to get them, or because we want to avoid them. That’s the way most humans employ vision, but artists are different. They use vision as a means of exploring the world in which they live. When I paint objects, I paint them not for the objects themselves, but for the emotional influence they have on others, and that’s an important part of communication.

Art is a window on how we see things, and not just with our eyes. It’s how we frame an image of the universe in which we live. If I’m looking at something as an uninformed viewer, I’m seeing it for acquisition and avoidance. Generally, we look for things either because we want to get them, or because we want to avoid them. That’s the way most humans employ vision, but artists are different. They use vision as a means of exploring the world in which they live. When I paint objects, I paint them not for the objects themselves, but for the emotional influence they have on others, and that’s an important part of communication.

Early on, I developed a theory about painting that works irrespective of the type of painting a person does. When a viewer looks at the art, does his mind want to go in the painting and play? If you are doing a landscape, for example, does the viewer see it and want to go in the painting and see what’s on the other side of the hill or behind the trees? If so, I think it’s a successful painting.

Absolutely.

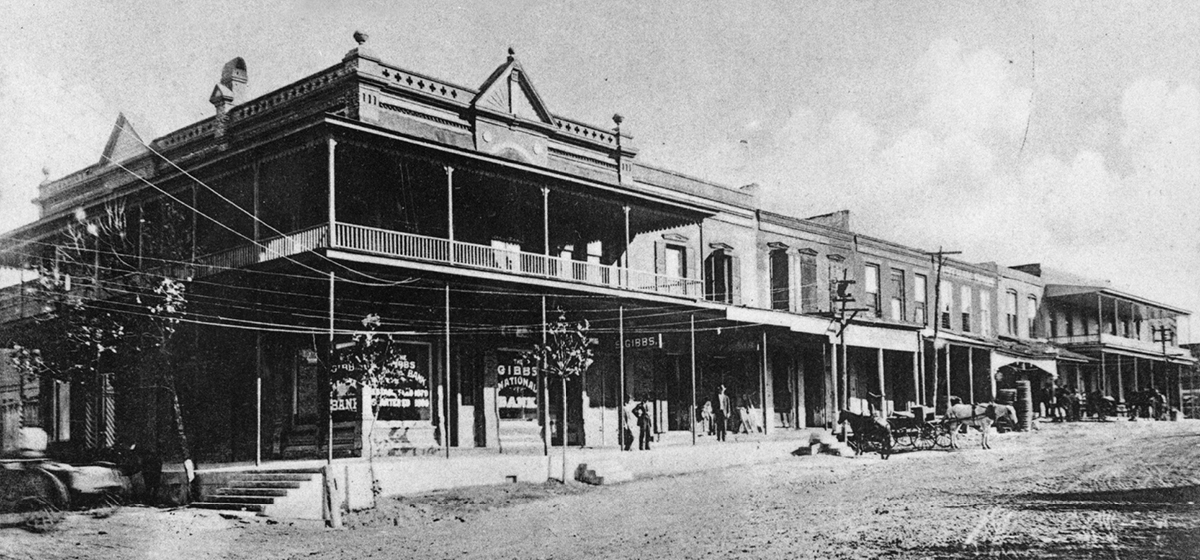

It was the most beautiful public building in the state of Texas. I’ve never seen any other building that was such an exalted piece of three-dimensional structure. I know many people who grieved over it when it burned. It wasn’t just a building; it was more like a personality.

One of the things I wanted to explore was the stained glass. I painted it such that there appeared to be lights on inside, in the hallways and beyond the classrooms. I wanted the viewer to want to go into that space to explore what else there is to see. It’s what I do when I do a historic painting. I invite people to be curious about what was inside that space.

If people want to learn about Lee Jamison the painter, which work should they see first?

If people want to learn about Lee Jamison the painter, which work should they see first?I think you’d have to come to a show. I’ll be featured in your heART of Huntsville program in September and October, I’ll have a show in the LSC at SHSU in October, and I’m in the planning phase for a future Wynne Home show. I encourage people interested in art to come see those works.

I’d like to do more work on Texas history. There are so many stories about life on the Texas frontier that I think people should understand better.

Art is foremost a communication skill. We know that humans participated in art some 70,000 years ago, long before we had written language. Language has gotten a grasp on our common mind and it’s taken over our use of story-telling. But art is capable of that, too. It was part of the classical education until about 150 years ago. Some of the best sources I have for what port facilities looked like on Texas rivers is from Stephen F. Austin’s sister, who drew pictures on all of her letters. We know what Texas looked like from William Bollaert’s (a 19th century polymath from England) images. We owe a similar debt to Seth Eastman, who drew images of the Alamo and San Antonio in the 1840s. That’s really all the information we have there, so we’re deeply indebted to these people for their visual images, which can tell stories that simply cannot be told by words alone.

For those interested in learning more about Lee Jamison’s art, the heART of Huntsville program will highlight many of his works in the context of Huntsville art in general (for more information, contact Mike Yawn at 936-294-1456); SHSU will feature his work in the LSC Art Gallery from October 2-14, 2016; and he is in the planning stages for shows at the Wynne Home and other area galleries.

SHSU will feature Jamison’s work in the LSC Art Gallery from October 2-14, 2016. For more info: (936) 294-1456