Tommy Moore spent more than four decades working at his family’s business, helping build the company’s sales to more than $50 million a year. For most professionals, that would be quite the career, but Moore’s passion for football helped him build a dual career officiating football games. His “second career” has lasted half a century, during which he has officiated games at the junior high, high school, college, and professional levels—including the Super Bowl.

You’ve been involved as an official in football for a long time. Did you ever play the sport?

You’ve been involved as an official in football for a long time. Did you ever play the sport?I played high school ball at McAllen High School. I was first team defensive back, second team wide receiver, and third team quarterback. We had a pretty good team, but we got beat by the state champs in the playoffs. We would have won, but the officials cheated us [smiles].

I graduated high school in 1961, and attended Stephen F. Austin, where I earned my BBA. I also did some work at Stanford with their Wholesale Distribution Program. I worked for my family business, the Moore Supply Company, wholesale distributors for plumbing, pipe, valves, and fittings. It’s based in Conroe, Texas. By the time I retired, we had 50 branches and were doing about $50 million in business. My son runs the company now. I’m retired, which means they call me and ask a lot of questions, but they don’t send me any money.

Football officiating was a passion, but it’s not a full-time job like major league baseball. When I was in college in the early 1960s, I officiated some intramural games. I started officiating junior-high games in 1967.

Oh, 10 or 15 dollars. The money gets better as you move up the ranks, but if you get into it for the money, you may be missing the point. The profession requires a lot of commitment. The games at the junior high, high school, and college levels mean a lot to the players, parents, and fans…and if they’re not a big deal to officials, they need to do something else. I tell younger officials to bring their “A-game” to the junior-high games and treat them just as important as they would for a championship game. Officials get to the next level by doing well and by receiving help from veteran officials. No one gets anywhere in officiating without someone helping them. When the veteran officials see you do well at one level, you get a shot at the next level. I was asked to officiate at the high-school level, then junior college, then the Southland Conference, and then the old Southwest Conference.

I worked full time, but I officiated at every opportunity. I usually worked junior high games on Mondays and Tuesdays, then freshman or junior varsity games on Thursdays, a high-school game on Fridays, and a junior college or college game on Saturdays. My uncle used to say, “If you worked as hard at the family business as you do at football, we’d make a lot more money.” [Chuckles] But working the football games was good for the business in a way, too. People around the state follow football, so it was a good way to start and carry on conversations.

Travel is a big part, particularly in high school, because it builds camaraderie among the officials. When you do high-school games, you travel together more, and you discuss the games on the road afterward. In college, officials often travel separately because they are coming from different cities.

They are all fun, but the college football atmosphere is hard to beat. The college campuses bring a lot of energy to the game. But in the NFL, it’s fun to go to Green Bay. Football is what they do there.

There are clinics and camps in the offseason, but they are for high-school and college officials. The lower levels are the training grounds for the higher levels.

Thinking about the technical aspects of the game, what preparation is necessary to officiate a football game?

Thinking about the technical aspects of the game, what preparation is necessary to officiate a football game?Officials have to learn the rules, of course, and for each game they arrive early for pre-game conferences. In high-school, officials have to arrive at least two hours prior to game time; in college, it’s at least four hours. In the NFL, it’s even earlier.

There’s something to that, and the NFL has done studies on putting a laser on the goal line or even putting a chip in the football. But not a lot of high schools have that technology. A lot of the technological improvements have been made in the area of safety. We now have equipment on the sidelines that can save lives and, in fact, we had an official last year who would have died on the field were it not for the trainer and a defibrillator.

There’s a distinction between the rules and the mechanics. Mechanics involve where to stand and where to move. Each official is responsible for a particular focus, and they must move in a manner that allows them to observe the action for which they are responsible, and then to apply the rules appropriately.

There’s more good sportsmanship on the field than there is the bullying that you hear about. The referee and the umpire are close to the action, and they do a lot of communicating with the players to have a presence. They engage in preventative measures to keep things from getting out of control. We want the players to play, but that doesn’t mean to let them fight, and there’s a line in there. The good officials know which side of the line to be on.

I worked the University of Houston vs. University of Arkansas game in Little Rock, back when Andre Ware was playing. Arkansas won 50-45, and it was one of the most exciting games ever played. I also worked the BCS National Championship Game the last time Notre Dame won it all. And I’ve worked NFL playoff games and a Super Bowl. But I think the biggest thrill was working the Texas 5A State Championship. We have about 5,000 football officials in the state, and we spend a lot of time together in meetings, and we all know each other. And when you officiate a game like that, you can’t help but think, “I’m doing this game for all the Texas officials, for everyone who has helped me, because I wouldn’t be here without that help.”

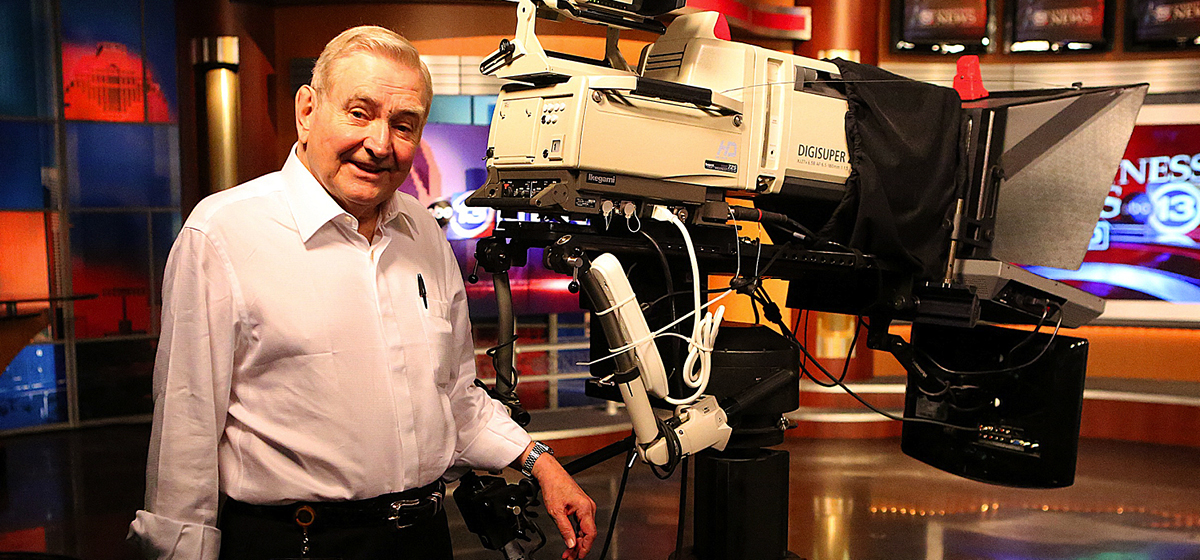

Tommy Moore was part of the crew selected for Super Bowl XLV in Dallas in 2011, Pittsburgh vs. Green Bay

In high school, we have a draft system for selecting officials; in college and the NFL, a supervisor assigns the crews to the game. Normally, you don’t go to a city more than once a year, and if you happen to see a team twice, you see them once at home and once on the road, and probably at least six to eight weeks apart. For the NFL playoffs, officials are selected by grades. The top graded official at a position plays the Super Bowl. The second and third work the championships, and so on, down to the wildcard. I was part of the crew selected for the Super Bowl in Dallas in 2011, Pittsburgh vs. Green Bay.

The biggest difference is that you aren’t officiating the play. You address the ruling on the field. In officiating on the field, you make the rule. In replay, you ask, “What was the ruling on the field, and was it right?” You watch it two or three times on replay and either confirm the ruling on the field, reverse the ruling on the field, or determine that the decision on the field stands because there isn’t sufficient evidence to overturn it.

As an official, you cannot be a shrinking violet. There are times you have to be demonstrative in your signaling because it makes the game play better. But you don’t want to be a ham.

[Laughs] Occasionally, we have some humorous things happen on the field. At one game at SMU, we had a referee (who was a federal judge) rule against the SMU coach for a substitution infraction. He had one of his crew members go tell the coach that his action was a “subterfuge.” The official started to run over to the coach, but he came running back and said, “I’m a PE major, and that coach is a PE major, and neither one of us knows what a ‘subterfuge’ is.”

As officials, our goal is the same as the players—to do our best. Consistency is key. What’s a foul on the forty-yard line is a foul on the five-yard line. Officials need to know the rules and how to apply them. They need to have the mechanics, knowing where to move on the field. They need good judgment. And they need what we call “it.” “It” is field presence. As an example, I have a friend and colleague, Mike Young, and he has “it,” as do all good officials. When coaches see Young on the field, they stop worrying about the officiating and focus on coaching, and when everyone is doing what they are there to do, the game is much more enjoyable for everyone.