One way to learn what it’s like behind bars in a Texas prison is to commit a crime, be convicted, and serve time. A much better strategy is to visit Huntsville’s Texas Prison Museum, which offers a rich behind-the-scenes look at the Texas prison system and its long history. Whether you want to learn about the Goree Girls, prison contraband, the Texas Prison Rodeo, prison artists, or “Old Sparky,” the Texas Prison Museum offers a sometimes disturbing, sometimes inspiring, and always fascinating look at prison life in the Lone Star State.

One way to learn what it’s like behind bars in a Texas prison is to commit a crime, be convicted, and serve time. A much better strategy is to visit Huntsville’s Texas Prison Museum, which offers a rich behind-the-scenes look at the Texas prison system and its long history. Whether you want to learn about the Goree Girls, prison contraband, the Texas Prison Rodeo, prison artists, or “Old Sparky,” the Texas Prison Museum offers a sometimes disturbing, sometimes inspiring, and always fascinating look at prison life in the Lone Star State.

The History

The Texas Prison System was created in the 1840s and accepted its first inmate in 1849, when a hapless horse-thief from Fayette County found himself behind the newly-built bars in Huntsville. Over the years, the prison system saw its share of history unfold—there were prison breaks and prison reforms; criminals both infamous (e.g., Henry Lee Lucas) and famous (e.g., David Crosby); a popular rodeo, art show, and baseball.

By the late 20th century, interest in the system’s history began to take hold. Artifacts were put on display at the Criminal Justice Center at Sam Houston State University for a few years and, in 1989, the Texas Prison Museum opened on the downtown square in Huntsville, just blocks from the Walls Unit.

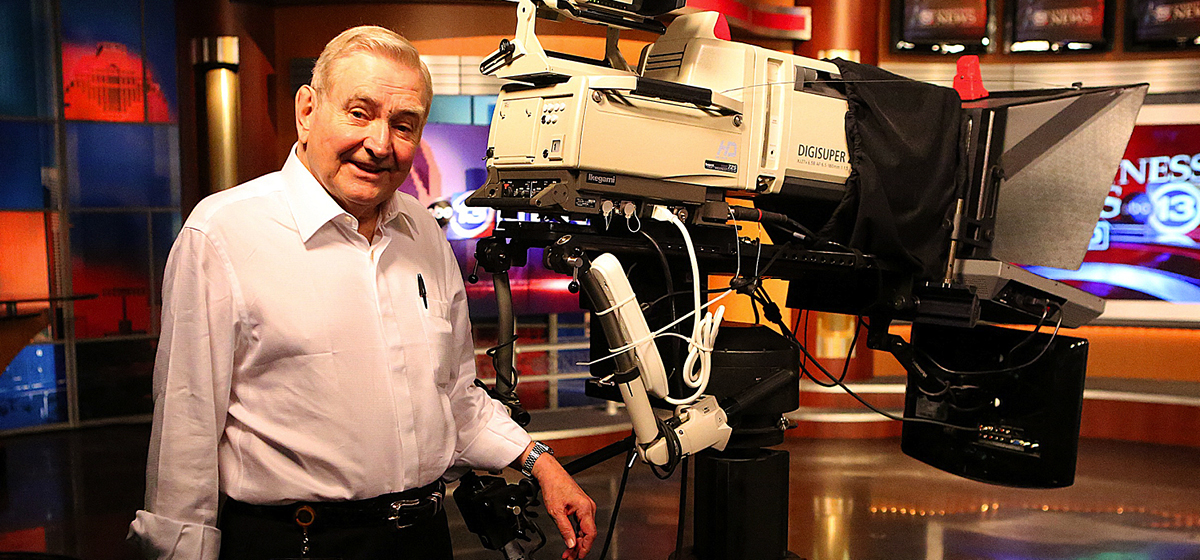

It was slow going in the early years, as museum staff explored what kind of demand there might be for a museum about prisons. “There weren’t a whole lot of visitors in the early days,” noted Jim Willett, former warden of the Walls, who now serves as director of the museum. “It was a good day if you could get two dozen people in the building.”

That changed in 2001, when the museum moved to its present location on Highway 75. The location change, according to Willett, and “the hard work that many people put into getting the museum established” laid the foundation for what is now one of East Texas’ most successful attractions. The museum draws more than 31,000 visitors annually, while also serving as a leading center for research into Texas prison history, developing educational and community programs, and hosting numerous special private events.

The Exhibits

“Many people come here with the idea that they want to see ‘Old Sparky,’” said Willett. “But they’re not here long before they find something they spend a whole lot more time exploring.” Nonetheless, the electric chair is a centerpiece of sorts at the museum. Following changes in the state’s execution laws in 1923, the Texas prison system used the electric chair exclusively for executions from 1924-1964, during which period 361 inmates were put to death.

“Old Sparky” is housed in a sparsely furnished, brick-enclosed space at the center of the museum. With spare overhead lighting illuminating the wooden structure, leather straps and metal clasps, the image is disturbing, even frightening. “The exhibit,” according to Willet, “closely resembles the setting in which Old Sparky was actually used at the Walls Unit,” a claim borne out by photographic evidence also on display.

But, as to be expected in a prison museum, the electric chair is not the only disturbing artifact among the exhibits. One of the more intriguing displays is “prison contraband,” which contains an operating pipe shotgun; a gavel that conceals a shiv; an alcohol still; a flip-flop with a thick sole used to hide a shank; and even homemade tattoo machines.

Prison contraband was used in the most notorious of Texas prison crises: the Carrasco hostage incident, one of the longest hostage-taking sieges in U.S. history. In 1974, Fred Carrasco and two other inmates took more than a dozen hostages at the Walls Unit, holding them for 11 days. The standoff culminated in a shootout resulting in the death of Carrasco, another of the perpetrators, and two hostages: Elizabeth Beseda and Julia Standley. The incident is covered in detail in the Museum, accompanied by photographs and artifacts such as Carrasco’s cane, guns used in the standoff, and one of the protective helmets worn by the hostage takers.

Also ominous is the replica prison cell, replete with stainless steel toilet, institutional lighting, and bunk beds. Visitors are invited to enter the cell and close the door, but even in the museum setting, few visitors linger in the cell or enjoy the clang of closed freedom.

Such exhibits may leave the impression that the museum is a dark and foreboding venue or perhaps simply a cabinet of historical curiosities. But the museum offers equal time to uplifting aspects of the correctional experience. “People are surprised,” observed Willett, “that there are some inspiring things in here; it’s not all dark and dreary.”

One of the more celebrated events in prison history was the Texas Prison Rodeo, which began in 1931 and continued for more than half a century. The competitions included bull riding, saddle bronc riding, and bareback bronc riding, but perhaps the most popular event was the “Hard Money Event,” a contest involving 40 inmates who competed for a sack of money tied between the horns of a bull. Apart from the competitive spectacle, there were celebrity performers such as Dolly Parton, Johnny Cash, John Wayne, Reba McEntire, Steve McQueen, Willie Nelson, and George Strait. In peak years, the rodeo brought in more than 100,000 people.

The prison’s art program also brought light and color to the lives of inmates and art lovers alike. “I worked for Windham when the art program was up and going,” recalled Sandra Rogers, the museum’s archivist/historian. “The inmates produced poetry, arts, and crafts, and we have some of their creations at the museum. Some of our more interesting sculptures, for example, are made from matches. They are intricate and show real craftsmanship.” Perhaps most impressive is a chess set, carved from soap, featuring chess pieces in the form of guards and inmates.

With increasing numbers of visitors attracted to the museum, plans for expansion are on the horizon. According to Willett, the museum may be able to add space—up to 5,000 square feet—within the next five years, approximately doubling the amount of display space. Although planning is in preliminary stages, possible exhibits include a historical video room, an expanded rodeo display, and increased space for prison art, among many other possibilities.

Research

Such an expansion would also allow for additional office space and more room to conduct research and to store artifacts, a prospect that delights Rogers. The existing storage space contains thousands of documents, including photographs of early Huntsville; minutes from prison board meetings; employee records; and mail to prison musicians, including the “Goree Girls,” whose music aired on WBAP in the 1930s and attracted approximately seven million listeners weekly—as well as some marriage proposals.

Amidst these back-room documents is an assortment of additional artifacts. There’s the spare old-school cotton scale, numerous rodeo souvenir programs, and (next to the “edible crop schedule”) you’ll find test light bulbs for the old electric chair. It’s an intriguing assemblage.

Research is also conducted directly on behalf of the public. For a small fee, museum staff comb through convict ledgers, scouring intake forms for the inmate’s name, body markings, sentencing, and the like. “People doing genealogy work sometimes learn their relative was incarcerated, and they want to know more,” noted Willett. “Staff members work with them to provide the information.”

The museum also hosts “old-timer” meetings, inviting former prison employees who gather and share stories. “They tell wonderful stories of family outings,” said Rogers, “that reflect the cohesiveness of the employees in the past. Many of them actually lived on the units, and they and their families spent a lot of time together. It is a reminder of the human aspects of the system.”

Museum staff are also a source of information and a reminder of the “human aspects of the system.” Many previously worked for TDCJ in some capacity, and they now work in their “second careers” preserving and promoting the institution’s history. Willett, for example, spent 30 years in jobs that ranged from correctional officer to warden. Now, as director of the Texas Prison Museum, he finds much to be grateful for: “I don’t have to worry about stabbings,” he told a reporter from The Texas Tribune. “I certainly don’t have to worry about escapes, and my staff really likes being here. It’s just the best place in the world for me to be.”

The museum is open Monday through Saturday from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., and Sunday from noon to 5:00 p.m. Admission is $4 for adults, with lower fees for children, active military, SHSU students, and TDCJ employees and retirees. For more information, call (936) 295-2155 or visit txprisonmuseum.org.