Photos by Kevin Black Photography

Photos by Kevin Black Photography

On a cold January day, a visit to Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site finds its once-bustling Ferry Street quiet. Students and visitors meander through Independence Hall, absorbed in the tales and truths of yesteryear as told by interpreters dressed in period style clothing. For that moment in time, all need for cell phones and fingertip technology is gone, and the respect the significant Texas landmark deserves is reverently given.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the park, and the 180th observation of the signing of the Texas Declaration of Independence. It was on these grounds, beginning March 1, that 59 delegates met for 17 days during the Convention of 1836 in order to write a constitution and establish an independent government.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the park, and the 180th observation of the signing of the Texas Declaration of Independence. It was on these grounds, beginning March 1, that 59 delegates met for 17 days during the Convention of 1836 in order to write a constitution and establish an independent government. They worked day and night, through fear and uncertainty, knowing Mexico’s merciless General Santa Anna was only 150 miles—a few days’ march—away.

They worked day and night, through fear and uncertainty, knowing Mexico’s merciless General Santa Anna was only 150 miles—a few days’ march—away.

After the March 6 fall of the Alamo, while many terrified locals fled the oncoming Mexican army during what became known as the “Runaway Scrape,” the delegates stayed, finally reaching an agreement and adopting the Constitution for the Republic of Texas on March 17, 1836. The new administration served the Republic of Texas from 1836-1846.

The way it was

Citizens returned to Washington only after the Texans’ victory during the Battle of San Jacinto, finding a town that was unharmed and undisturbed.

Citizens returned to Washington only after the Texans’ victory during the Battle of San Jacinto, finding a town that was unharmed and undisturbed.

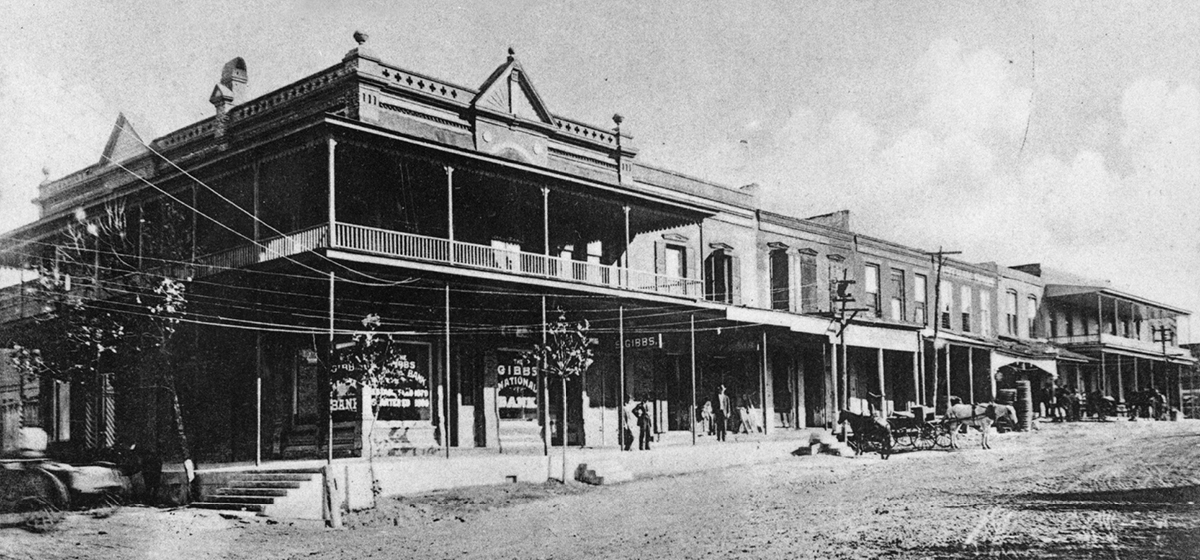

At the time of convention, Washington had about 200 residents. Offering the free use of a meeting hall for the delegates by the town promoters proved to be beneficial to the town. Soon after, it became both a thriving political center and a commerce hub, eventually claiming a population of over 900.

Steamboat traffic along the Brazos River was instrumental in the town’s growth, as Washington was navigable to the coast and was therefore relied on for trade by the early Texians. Stagecoach lines conveniently connected the cotton-rich community to neighboring towns. There were hotels and taverns, doctors and lawyers, tailors and dressmakers. The sleepy little village’s Ferry Street was suddenly active, with all the business of daily living.

From 1842-1845, Washington served as the last capital of the Republic of Texas. The community’s heyday, however, was short-lived. A poor decision to decline an offer to bring the railroad tracks to town became the beginning-of-the-end for the bustling trade center. Steamer travel dwindled because of the railroad competition, and the town began to wither.

From 1842-1845, Washington served as the last capital of the Republic of Texas. The community’s heyday, however, was short-lived. A poor decision to decline an offer to bring the railroad tracks to town became the beginning-of-the-end for the bustling trade center. Steamer travel dwindled because of the railroad competition, and the town began to wither.

Fortunately, by the 1880s, the abandoned buildings and overgrown streets became of interest as a historical site; and in 1916, the State of Texas acquired 49 of today’s 297 acres for its preservation.

History, alive and well

Walking along the park’s winding paths, you get a sense of what life was like at the time Texas became independent. There’s the serenity of the huge oaks, the remnants of Ferry Street that lead you to the river bank’s overlook, and the smell of earthy wood as you enter Independence Hall.

Walking along the park’s winding paths, you get a sense of what life was like at the time Texas became independent. There’s the serenity of the huge oaks, the remnants of Ferry Street that lead you to the river bank’s overlook, and the smell of earthy wood as you enter Independence Hall.

On Living History Saturdays (third weekend of each month), the Hall comes alive through professional interpreters and volunteers. Jana Wesley sits at an open window on a cowhide chair, showing a visiting young girl how to make a doll from a small piece of cloth. She explains that “church dolls” were so named because, if they were dropped during a Sunday service, they wouldn’t make any noise.

Meanwhile, Park Ranger/Interpreter Adam Arnold describes the rudimentary practices of early medicine, including the use of strategically placed leeches and maggots, and bloodletting.

Meanwhile, Park Ranger/Interpreter Adam Arnold describes the rudimentary practices of early medicine, including the use of strategically placed leeches and maggots, and bloodletting.

He explains that poor sanitation often resulted in cholera, dysentery, and typhoid. Yellow fever, malaria, and smallpox were a constant worry. It was a time when folks used whatever was available to them to promote health and well-being— including taking cinnamon for fever and consuming lead powder to enhance beauty and slow down the aging process.

Samples of weaponry lay upon the rustic table, next to an inkwell and quill pen where visitors are encouraged to try their hand at calligraphy.

Samples of weaponry lay upon the rustic table, next to an inkwell and quill pen where visitors are encouraged to try their hand at calligraphy.

On any given day, interpreters dressed in period clothing also greet visitors at Barrington Living History Farm. Barrington Farm was the home of Anson Jones—the last president of Texas. Jones lived there with his wife Mary, four children, extended family, and five slaves.

The property consisted of the family home, an outdoor kitchen, a smokehouse and cotton house, two slave quarters, and a barn. Today, each are on display, and the farm is alive with gardens, livestock, and women washing clothes on washboards, cooking “farm to table” foods, knitting, and sewing.

Each employee/volunteer is intent on authentically demonstrating a way of life from 150 years ago.

Each employee/volunteer is intent on authentically demonstrating a way of life from 150 years ago.

Barb King, who has worked at the park for eight years, is clothed in handmade winter clothing, including the scarf she knitted from wool that was sheared, spun, and dyed at the farm. In an outdoor kitchen, she is cooking freshly butchered sausage and a mixture of vegetables in cast iron pots over an open hearth, explaining why what she does matters.

“The most important thing about living history and the kind of experimental archaeology we do is that it makes things relevant; seeing the way someone cooks certainly brings it to life, much more so than just seeing a static display.”

“The most important thing about living history and the kind of experimental archaeology we do is that it makes things relevant; seeing the way someone cooks certainly brings it to life, much more so than just seeing a static display.”

A deer hide is tanning outside a replica of one of the slave quarters and, across the way, meat hangs in the smokehouse. While the garden shows limited signs of crops during the winter season, spring will find heirloom seedlings fighting their way through the freshly tilled soil.

The cracking sound of a handcrafted leather whip breaks the serenity as Ben Baumgartner demonstrates its use and purpose, taking every precaution to stress that the whip never touches the animal—a sad misconception. Instead, it’s used merely for guiding the oxen or other livestock.

The cracking sound of a handcrafted leather whip breaks the serenity as Ben Baumgartner demonstrates its use and purpose, taking every precaution to stress that the whip never touches the animal—a sad misconception. Instead, it’s used merely for guiding the oxen or other livestock.

Visitors delight at the simple pleasures of farm life found here that can’t be found in the city. Noisy guinea fowl, long-horned oxen, messy pigs, and chickens (including the always-good-for-a-laugh Kramer) make the experience memorable.

Gone, but not forgotten

The people who volunteer or work at the park show a genuine love for everything it represents. Even those who leave can’t seem to stay away for good. A brisk walk through the park with their dog Bosco is routine for longtime previous employees Pam and Tom Scaggs, now living permanently in Washington. Their path leads them past Independence Hall down the crooked little Ferry Street to the La Bahia Pecan tree.

The people who volunteer or work at the park show a genuine love for everything it represents. Even those who leave can’t seem to stay away for good. A brisk walk through the park with their dog Bosco is routine for longtime previous employees Pam and Tom Scaggs, now living permanently in Washington. Their path leads them past Independence Hall down the crooked little Ferry Street to the La Bahia Pecan tree.

Pam’s sentiment for the tree’s significance is genuine.

“Can you imagine all this old tree has witnessed?

From the day the nut, which grew to be this tree, was planted by a squirrel for a later date, or simply fell from a travelers bag and germinated on its own, this tree has witnessed quite a bit of history.

It saw famous folks like Davy Crockett passing through Washington on his way to the Alamo. It saw many of the delegates to the Convention of 1836 who declared Texas an independent country, the Republic of Texas.

It saw famous folks like Davy Crockett passing through Washington on his way to the Alamo. It saw many of the delegates to the Convention of 1836 who declared Texas an independent country, the Republic of Texas.

It listened as little kids ran around its trunk, playing hide and seek, or gathering its pecans so momma could use them for cooking.

It smelled that smoke coming from the fireplaces and fire pits as momma made supper or boiled laundry.

It watched as the Washington town folk fled in terror during the Runaway Scrape.

It watched as the Washington town folk fled in terror during the Runaway Scrape.

It witnessed the town grow from a little frontier town into a town of 1000 people and center of commerce. It also witnessed it die as the railroad passed it by.

And now it sees and hears the visitors at Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site, who come to learn all about what this beautiful, old tree could tell you, if it could only talk.”

March 5-6, 2016

Each year in March, festivities are held in honor of Texas Independence Day. This year promises to be bigger and better than ever in recognition of the centennial celebration of the Birthplace of Texas. There will be reenactments, music, musket and cannon firing, and the Park Association’s Official Program.

Each year in March, festivities are held in honor of Texas Independence Day. This year promises to be bigger and better than ever in recognition of the centennial celebration of the Birthplace of Texas. There will be reenactments, music, musket and cannon firing, and the Park Association’s Official Program.

But aside from the annual fanfare, every day is worthy of a visit. The Visitor Center’s “Gallery of the Republic” is a museum in its own right, in addition to the on-site Star of the Republic Museum.

The Republic of Texas complex consists of Independence Hall, Barrington Farm, and Fanthorp Inn State Historic site in Anderson, Texas— just a short 20-minute drive from the main park. According to Superintendent Catherine Nolte, 90,000-100,000 folks visit the complex annually.

The Republic of Texas complex consists of Independence Hall, Barrington Farm, and Fanthorp Inn State Historic site in Anderson, Texas— just a short 20-minute drive from the main park. According to Superintendent Catherine Nolte, 90,000-100,000 folks visit the complex annually.

Nostalgia abounds at each location and affords visitors an escape from their hectic, daily routine. Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site is a place where children can get a taste of country life’s bygone days—and it’s a place where vintage toys like checkers, stick horses and clay marbles are suddenly enough. Even if it’s just for a day…

For more information: tpwd.texas.gov/state-parks/washington-on-the-brazos