Joel Phillips, Sr. was my 5th great-grandfather and my Daughters of the American Revolution Georgia Patriot. This story is as true as can be verified by oral accounts and history recorded. There are records of his bravery in battle and his Christian generosity. The most frequently recorded, and repeated, story is of the Sabbath Day that the Patriot boot met the Tory breeches.

My name is Joel Phillips, Sr. I am an American Patriot. The year is 1790.

I was born in Virginia in 1728. My wife Elizabeth and I met and married in North Carolina. We judiciously moved to Georgia in 1773 with 5 sons and 2 daughters, the youngest of which was 9 months old.

We settled on land ceded by the Cherokee, betwixt Little River and Kettle Creek, near Fort Heard, which later became Washington, Georgia. The forests abound in deer, black bear, wolf, wildcat, and small game, such as squirrel and rabbit. Quail are secluded in the underbrush, until they take flight with a mighty ruckus, and the clear, swift streams are full of fish.

My land is flanked on two sides by Cherokee and Creek Indian country, so I fortified the living quarters and outbuildings until our original property became recognized as Fort Phillips. In those days, we reasoned the only threat to our safety and well being would be from the Indians.

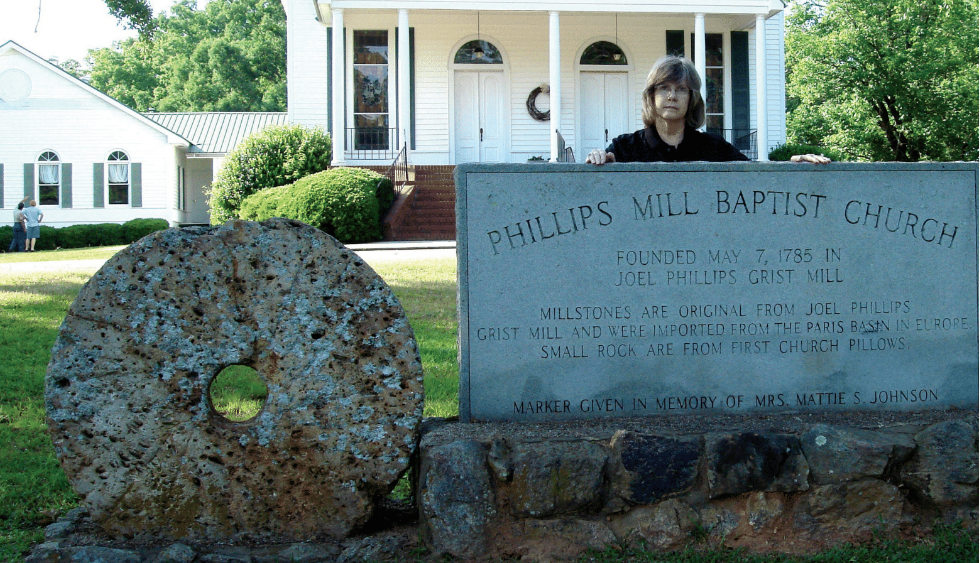

I put up a grist mill on Little River to supply my family’s needs, and those of the public, for wheat and buckwheat flour and corn meal. The mill stones were cut from rock found in the Paris Basin of the Seine River in France and made from sedimentary stone. After the stones were cut, they were transported to the Savannah area by boat and on to this area by ox cart.

In 1786, sixteen of my neighbors were holding church services in the mill, so I bequeathed the land on which Phillips Mill Baptist Church was built and helped to build it. My family worships there and we will likely be buried in the churchyard. Elizabeth has been a steadfast companion of good humour, and my offspring have made me very proud. I have endeavored to set an example for them as to how to be God-fearing, self-sufficient and resourceful, while being a contributing part of the community.

I was past 50 years of age when the Revolutionary War came to Georgia. I had no way to know, in the early years of the War, that I would be skirmishing my own Government in my own backyard.

There are many tales that I could tell about my life — some inspiring and some disheartening. But the story of the Battle of Kettle Creek is an account of the most harrowing time in my life–even more so than defending kith and kin from the Indians for nearly 10 years.

By 1779, Colonel James Boyd, with 600 British sympathizers (Loyalists or Tories), was on his way to covey up with the British Army in Augusta to bring Georgia wholly under the King’s control. The backwoods frontier of north Georgia proved to be difficult and severe for the British Army, in their dandy uniforms, whereas the terrain was as familiar as our old smocks to us. Our one thorny issue was a recent barrage of thunderstorms, most unusual for February, that saturated the ground.

When word reached the British that a few leathery farmers in North Georgia had formed a resistance movement in Fort Heard, Colonel Boyd was ordered to scout the area. The Tories were hard to miss with their numbers and their bright red jackets. That encounter was how the Patriots came to know that the Loyalists were already in Wilkes County.

In a secluded area near Kettle Creek, on the night of February 13, 1779, Patriot troops, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Elijah Clarke, Colonel John Dooly, and Colonel Andrew Pickens, encamped. Colonel Pickens had 200 South Carolina militia, while Colonel Dooly and Lieutenant Colonel Clarke, my commanding officer, had 140 Georgia militia in the area, primed to overtake the Loyalists, who were far too close to home to suit us.

On the morning of February 14, 1779, Colonel Boyd and his men were camped beside a bend in the recently flooded Kettle Creek. The enemy was sleeping on my land. They had sentries posted, but their horses were grazing. Most of the men were busy slaughtering Phillips cattle or scavenging the countryside for food on my property. The political injustices of the Government had now become personal.

Early that morning, with only 340 men, The Patriots launched a surprise attack on the British forces bivouacked at Kettle Creek. The Tories had slept warmed by a fire, but we had relinquished comfort for concealment. There were three Patriot columns; Colonel Dooly was on the right, Colonel Pickens was in the middle, and I was following Lieutenant Colonel Clarke on the left. Colonel Pickens had sent an advance guard ahead of the columns to scout for the British. Our Patriot scouts happened upon the Loyalist sentries and opened fire.

The gunfire alerted Colonel Boyd and quashed our surprise attack. Colonel Boyd rallied his men, took a small group and advanced to a nearby hill, where they waited behind rocks and fallen trees for cover. Colonel Pickens continued his advance to the top of the hill, but the two columns under Colonel Dooly and Lieutenant Colonel Clarke were hindered by the high creek water, swamps, and cane breaks. On the approach of Pickens Patriots, the Loyalists opened fire, and the lead men of the Patriot column immediately fell victim to the first rounds.

It was bitter anguish to hear our fellow men yelling, while we were impeded in getting to the battle. From the location of the cries, it sounded as if our side was losing. We struggled on, even harder–determined to save this patch of Georgia from the tyranny of the British. Damn the flooded creek and damn the cold. It may sound far-fetched to yearn to arrive at a battle, but that’s just how we felt. Our very independence was at stake, and we were fully prepared to die for it.

By what may have been Divine Intervention, a Patriot musket ball mortally wounded the British commander, causing panic among the Loyalist militia, who pulled back pell mell to the camp in the ravine. As Colonel Pickens’ men gained the high ground above the camp and began to fire from above, the Loyalists realized their mistake and tried to escape by crossing Kettle Creek.

Just as the forward Loyalist line made it to the far side of Kettle Creek, Colonel Dooly’s men broke into the open. Suddenly, our column, too, broke out of the swamp, and the battle was on. By my God, it was brutal. The Loyalists began a second retreat, more disorderly than the first. After three hours of perilous fighting, on both sides of Kettle Creek, disorder turned into defeat. We had defended Kettle Creek and, by the grace of God, only 7 Patriots were killed.

Of the 600 Loyalist troops, at least 20 died at Kettle Creek and another 22 were taken prisoner. The rest had, on the face of it, seen enough of Georgia. Colonel Pickens was later quoted as saying, “Kettle Creek was the severest check and chastisement the Tories ever received in Georgia or South Carolina”.

That was a mighty fearful time in my life and, even though I am a Christian, I am not a man to forgive and forget easily. To leave your family to go to war, only to return and hear about the suffering and malice endured by your beloved wife, at the hands of the enemy, is mighty hard to abide.

My intense loathing of the British festered like a boil, long after the war ended. When we were building Phillips Mill Baptist Church, we had placed the log floor joists, but did not yet have the structure floored. The congregation, in the meantime, was sitting on those logs, which were the sleepers for the building. Just before services one Sabbath, I was in the church, kneeling in prayer, when a Tory entered. I pray that the uncharitable act that followed will be soon forgotten.

With God as my witness, I rose from my knees, stepped from log to log to where the Loyalist was sitting, and ousted the intruder. Taking him by the scruff of the neck, I escorted him back across the room and added a resounding kick at the door. When I resumed my prayers, I did so with the apparent approval of the entire congregation.

My faith assures me that God has forgiven me, and he may also have approved.